Big Empathy

By Tom Atlee

March 2015

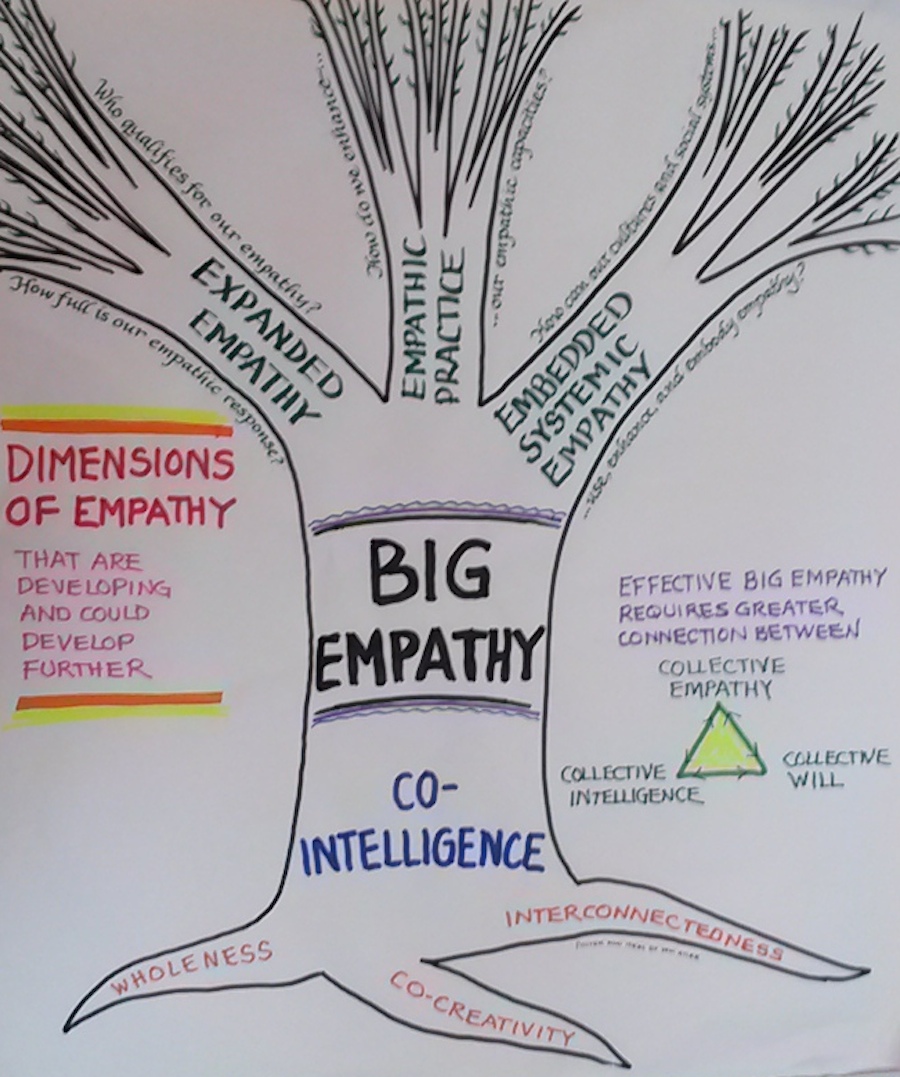

This essay describes in some detail the rationale for and factors

involved in expanding our empathy in three ways:

1. widen our "circle of care" to include more beings of

more species over greater time periods;

2. become better practitioners of empathy; and

3. embed empathy in our cultures and social systems.

These ideas are explored from other angles in

Tom Atlee's talk Big Empathy: Creating

a Wise Democracy and a Caring Economy (mp3).

EMPATHY AND EVOLUTION

Looking at empathy in an evolutionary context, we may notice the

following:

The whole point of empathy - the reason it evolved - was to help

us bond and function in cooperative, mutually supportive groups

- couples, families, tribes, clans - as an "us" that contrasted

with others who were "not us". Empathy makes us want to

relieve each other's suffering and to enjoy each other's joys. We

can feel what each other is feeling and understand more about what

each other needs, motivates us to help each other out. Clearly,

we couldn't survive if we responded that way to everyone and everything;

it would be too much; our attention and energy would be too dispersed.

Empathy was "designed" to operate within the boundaries

of our communities. It helped us define and maintain those boundaries,

and empathic communities survived to pass on their members' genes.

But as our tribes grew into towns, organizations, cities, countries,

civilizations, global economies - with their trade, war, mobility,

and associated uprootedness from any one place and culture - we

came into contact with Others with whom we needed to engage as part

of "us". Pluralistic cultures emerged promoting an expanded

sense of who "we" were - even to the extreme of "Love

thy enemies".

But another aspect of this cultural evolution undermined such feelings.

Empathy ties us to each other and make us "care too much."

That connectedness and sensitivity can make it harder to produce

efficiently, to consume mindlessly, and to feel free to pursue our

own personal aspirations regardless of those around us.

The 17th and 18th century Enlightenment facilitated a shift from

cultures based on tribe, community, and tradition to more individualistic

cultures using concepts like RIghts and Entitlements. Rights enable

us as sovereign individuals to define our independence from other

individuals and from our community or State. Entitlements are things

that the collective owes to us sovereign individuals. Our relationships

focus on rational material self-interest. Gone is the sense that

we are intrinsically mutually beholden to each other, that we are

fundamentally interdependent, and that our impulse to co-create

for mutual benefit is driven by our resonance with - and empathy

for - each other.

Something is clearly lost in this shift. While rights and entitlements

have fed the progressive legitimization, enfranchisement, and support

of the Other - i.e., of marginalized people, be they slaves, people

of color, poor people, women, immigrants, disabled people, people

of different beliefs, appearances, proclivities, etc. - this liberation

has been pursued and accomplished by category (of people), officially

and at arms length, not primarily by evolving personal and interpersonal

relationships and resonance between people of the margins and people

of the mainstream. Our primal, vibrant sense of embeddedness, of

belonging, of connection can easily be left to atrophy

unless we notice that it is withering and take action to counter

that ebb of our humanity.

In response to this we find movements emerging to reconnect with

each other, from communes to interfaith and interracial dinners

to Nonviolent Communication

and dozens of conversational methodologies. We find novels and performances

- Anna Deavere Smith's work

stands out - that introduce us to the inner and outer lives of people

unlike ourselves on the surface but so like us at some deeper level.

Similarly, we find the same kind of Enlightenment estrangement happening

in our relationships with place and nature. Most modern people live

in many different places during their lives, losing local rootedness

- that true embeddedness in the life, history, and destiny of a

place that produces responsible relationships with all the life

that lives there. Uprooted, we see humanity as separate and (ideally)

in control of nature. We exploit natural "resources",

dump our waste into natural systems, create substances that neither

nature nor we know what to do with once we're done with them, and

protect ourselves from nature's undesirable impacts on our lives

- like weather, disease, and famine - rather than coming to terms

with our place in the natural scheme of things. Unfortunately, nature's

impacts are vital to maintaining its balances. For example, famine

and deaths in any species limit unhealthy population growth and

decay and death feed the recycling of materials needed elsewhere

in the ecosystem. Pre-industrial human vulnerabilities helped limit

humanity's collective arrogance, which has lately been unleashed

by technological prowess, generating a competition between Nature

and Humanity. Our success at impacting nature while protecting ourselves

from its impacts is producing more dangerous impacts - from droughts

to disease-resistant bacteria - as nature increases its efforts

to bring our collective individualistic behaviors into its biospherical

balance.

We find our alienation from place being countered by community activism,

participatory care of the landscape and community and, in its most

eco-sophisticated form, bioregionalism and care for "the commons".

We find our alienation from nature being countered by everything

from scouting, outdoorsmanship, gardening, and the creation of National

Parks to declarations of the Rights

of Nature, animal rights movements, and wildlife and ecosystem

conservation efforts. For deeper responses, we have biomimicry,

deep ecology, nature

religion, evolutionary

spirituality, and a resurgence of shamanism

and respect for indigenous cultures. Systemic responses include

movements and technologies fostering sustainability, permaculture,

and eco-conscious monitoring of toxics, population,

ecological footprint, consumption, economic activity, technological

development, and more. There's a growing understanding that we are

part of nature and/or can live in sustainable partnerships with

nature - either of which requires a radical shift from our modern

dominator mind-set.

These trends are augmented by another manifestation of big empathy

which we can consciously develop: the experience of aesthetic, spiritual,

and nature-based resonance. When we are fully, immersively present

with the colors, textures, patterns, smells, tastes, forms of aliveness

and beingness in the world around us, they can evoke vivid emotional

and spiritual responses within and among us. We enter into the being

of person or thing - an animal, scene, rock, or work of art - in

ways that dissolve boundaries that make it "other", sometimes

even opening us into the unitary wholeness of the living universe.

Various psychedelic substances or exercises in being present or

being in the present moment can return us to this primal state of

empathy with the world around us, countering the distraction and

alienation of civilizational busyness. Even bringing more quiet

moments into our lives can give us a taste of this.

INDIVIDUALIZATION, DIVERSITY, AND THE COMPLEXITY

OF WHOLE SYSTEMS

As a general pattern, evolution - evolution beyond Darwinism, the

kind of evolution that's been going on since the Big Bang - seems

to love generating a wild diversity of molecules, organisms, ecosystems,

people, cultures, businesses, breakfast cereals, video games, and

nearly everything else. Evolution also loves weaving the diversity

it creates into more complex life forms and dynamic systems like

global economies, the global Web, and the global biosphere.

Both of these trends - diversification and integration - are complementary

features of the evolutionary journey towards ever-more complex forms

of wholeness. In the development of any whole, we almost always

find both increasing distinctness of the parts AND increasing interconnection,

interaction, and interdependence among those parts.

We see this in human development. We see "individuation"

unfolding in the "terrible twos" and in adolescence as

a young person struggles to craft a distinct self separate from

their family, even while they weave themselves into other social

units - into friendships, clubs, workplaces, relationships, tribes,

and more. Over time, if their development is healthy, they return

to their family as a unique whole individual in more or less peer

relationships with their parents and siblings, developing a new

family whole overlapping the other group wholes they are part of.

Empathy plays a role in bonding us into these groups, and in distinguishing

"us" from those with whom we feel little or no empathy.

As noted above, we find in the overall evolution of civilization

a similar developmental phenomena: Fragmenting dynamics like diversity,

individualism, alienation, mobility, etc., develop in tandem with

new (and reclaimed ancient) forms of connection, interdependence,

cooperation, and collectivity. Through the simultaneous unfolding

of these seemingly opposite dynamics, the society as a whole evolves

into novel patterns of complexity.

In my thinking about empathy, I stumbled upon an interesting dance

between the dynamics of oppression - patriarchy, colonialism, racism,

sexism, etc. - and the Enlightenment versions of capitalism and

democracy that celebrate and reify the individual. Oppression dynamics

bind a privileged part of society together into a group by viewing

the Other - i.e., certain oppressed and often exploited people,

organisms and eco-systems - as lesser forms of life that can be

treated as objects (by "Us") and for which we need feel

no empathy. Empathy is right for "Us"; control, exploitation,

or marginalization are right for "Them" (or "It").

This familiar divide-and-conquer, us-against-them (or us-over-them)

strategy taps into our deep tribal identity impulses and helps those

in power maintain their dominance and to carry out wars on "those

bad Other people". It has played a significant role in building

large complex societies that are held together by (among other things)

the force required to control the wildness and resources of nature

and the resistance of oppressed and conquered people. We can see

many examples of this dynamic in history and in current events and

social dynamics, both domestically and internationally.

THE DANCE OF EMPATHY AND ECONOMICS

This dance becomes even more intriguing and complex when we contemplate

the way money-based economics both manifests and transcends such

oppressive dynamics. In modern economies we see the dynamic of "empathy

for Us and control and marginalization for Them" in such phenomena

as corporate competition and the exploitation of people and nature.

In addition, there's the ubiquitous assumption that the money-based

economic system (rather than nature or our community) will provide

for our needs: We just need to live in it and support it with our

labor, our investments, our consumption, our votes, our educational

systems, and all our other individual and collective endeavors.

We can easily get the impression that with enough money, we don't

personally need each other; we get our needs met by "the economy".

Because of that, to a remarkable degree, the money economy doesn't

need force to function: Our utter dependence on it makes us cooperate

with it. All the economy needs to do is keep us sewn into its fabric.

(Obvious exceptions to this "no force" principle exist,

like the killing and imprisonment of minorities, organizers, and

whistleblowers, and movements and societies that resist market capitalism.

But here I want to explore the intriguing dynamic that makes economies

so powerful even without force.)

There's an interesting way that the money economy sometimes enhances

empathy. Profiteers benefit by including more and more consumers

in their markets. Nowadays their market activities extend worldwide,

drawing extremely diverse people into ever closer engagement with

each other - as workers, as investors, as consumers of popular (and

each other's) cultures and products. So we find multinational corporations

promoting multiculturalism, tolerance, and diversity trainings,

because these things support their profitable expansion into the

multicultural global marketplace. And markets have become multicultural

everywhere, thanks both to telecommunications media and the mobility

of populations; more of us increasingly live or experience our lives

more or less "everywhere" around the world.

Adding to this diversifying vector, the money economy promotes new

forms of both individualism and tribalism. It commodifies, alters,

remixes, and disperses diverse traditional cultures and pries people

out of those cultures to pursue their supposed personal expressions

and aspirations. But all too often people end up trying to fulfill

and present themselves to the world using the fads and options pushed

on them by the global economy, enhanced

by its growing capacity to customize everything. We get the

impression - especially if we have sufficient funds - that we are

"free to be me", independent from each other, from place,

and from nature - despite overwhelming evidence that that's a dangerously

false impression.

The economic system becomes the go-between, the medium, the mediator

between us and the world. Our former primary and immediate interdependence

with nature and with human community are being progressively replaced

by an economic interdependence woven out of our productive and consumptive

participation in complex artificial economic ecosystems, driven

always by money.

In this globalized culture, our empathy - still functioning for

most of us among our families, friends, and close colleagues - gets

stretched beyond our usual circles by charities, news, activism,

and advertising. We may feel guilty that we can't meet all the needs

of others that are pressed upon us in the media. We may start to

ignore or deny those needs. We may reach a point where, in order

to continue functioning in the business-as-usual economy, we have

to pull back and tone down our empathy, making it shallow or risking

"compassion fatigue". Many of us try to control this by

specializing in some community or cause within which we can effectively

practice our empathy while tuning out other needs and other legitimate

objects of our fellow-feeling. To help us see the results of our

caring, we tend to channel our empathy towards producing direct

benefits rather than long-term transformational change. Most of

us intuitively feel that the systemic causes of the suffering we

seek to address are too abstract, with tremendous obstacles and

delays involved in changing them.

In other words, the global money-driven economy has enhanced both

our diversity and our homogeneity, both our alienation and our connectedness.

It has both expanded and contracted our empathic impulses, reweaving

them for its own purposes and contributing to its own increasing

complexity and power. But the money economy is only one manifestation

of the fact that all social dynamics, cultures, and social systems

are two-edged swords, capable of enhancing and/or undermining our

personal empathic impulses. It is up to us to become more conscious

of this fact, and to use it to create a more empathic civilization.

We must especially become more conscious of how money can make us

feel we don't need each other and don't have to attend to the social

and environmental impacts of what we buy, produce, and invest in.

We must realize how wealth can seal us off from realities faced

by the less fortunate. We need to notice how mobility makes it possible

to move away from places, situations and people we don't like to

environments more to our liking, and how that creates not only comforts

but distances and boundaries in our hearts. We need to realize how

customized internet services reduce our exposure to other perspectives

- except through the eyes of partisan commentators with whom we've

chosen to align ourselves. We also can notice how public relations,

novels, movies and music are used to split us apart - or to bind

us together in unhealthy, oppositional ways - and to keep us ignorant

of the experience, concerns, and lives of those we come to see as

the Other.

There are limits to how far these alienating dynamics can go, and

we are reaching those limits. As a civilization we have grown in

our capacity to collectively generate complex harmful impacts that

overwhelm or bypass our natural empathic responsiveness. So much

systemically hidden harm goes on beyond the reach of our inborn

empathy that the original evolutionary logic that drove the emergence

of empathy in the first place is being brought into question.

In response, empathy is evolving - and needs to evolve more quickly.

We find that evolution, changing circumstances, social development,

and many dynamics of modern life are challenging us (a) to expand

our sense of who is "like" us and therefore worthy of

our empathy (during which process our sense of who "we"

are - individually and collectively - may expand, as well) and (b)

to develop personal competence in effectively exercising our empathy.

There is another aspect of this evolution: (c) creating systems

that embody expanded connection, caring, understanding, and validation

- even when when the people involved do not individually feel the

empathy that tends to motivate such connection and caring within

their close relationships. In essence, the systems themselves "practice

empathy". This involves embedding empathic caring dynamics

into our cultures and our political, economic, and social systems.

What does that mean?

The more social dynamics and social systems alienate us from each

other, the more important personal empathy and empathy-building

practices like Nonviolent Communication become. On the other hand,

the more we embed into our social systems and cultures consideration

for each other and the world around us, the less the chance that

personal lack of empathy - on the part of leaders or people in general

- will harm others or disrupt society or nature. Obviously, we need

to attend to both the personal and the systemic dimensions. But

at this point I want to explore some systemic manifestations of

empathy that promote authentic fellow-feeling, mutual relationships,

social support, and collaborative effort.... just to improve our

sense of what that means and how we might use such changes to make

the world better.

EMPATHY, ANTIPATHY AND SOCIETY

We all know empathy as a feeling. It engages our emotions and imaginations,

drawing us into other people's shoes, into seeing the world through

their eyes, into resonance with their experience. Whether or not

we agree with them, we taste what it is like to be them.

Empathy is intrinsically valuable for those of us who feel it. There's

a depth of humanity and warmth of connection that comes from feeling

empathy. We value that quality in our lives even despite the heartache

it sometimes brings.

But empathy is most valuable - and actually exists, thanks to evolution

- for the benefits it generates beyond the meaning and feelings

it gives us personally. As noted earlier, empathy produces important

blessings in the real world. It helps us understand each other so

we can work together better, so we can help each other better, so

we can struggle and celebrate together and work out our conflicts.

When we feel empathy, we don't see each other as objects nor distance

ourselves from each other's experience. We see each other as full

human beings like ourselves. Our life together, it turns out, is

better when we feel empathy towards each other.

So why do we so often fail to understand each other, to help each

other, to work out our conflicts? Why do we create distance and

objectify each other, seeing each other as less than us, even less

than human? Why do we tolerate the suffering that this imposes on

us and on others?

There are personal psychological reasons for this. Evolution hasn't

made us only empathetic. It has also made us want to be right, which

sometimes seems to require that we make others wrong. It has made

us defend ourselves and close down when we feel vulnerable or threatened

- or made us become habitually defensive, violent, and/or contracted

if we've been made severely vulnerable and damaged in the past,

specially in childhood or war. It has also made us care more about

others who are like us - or related to us, or part of our tribe

- than we care about those who are different or distant from us

- those Others. And all these psychological dynamics are used in

modern societies by people and groups who want to manipulate our

relationships with them and with other people and groups, and to

get us to behave in ways that benefit their interests.

So evolution has given us the capacity to feel empathy for each

other - and to feel antipathy or apathy as well. We have both potentials.

The often manipulated context in which we live shapes which of these

we manifest - in a given circumstance or habitually. The ways we

are brought up and educated, the stories our culture tells us, and

the ways our society is organized all shape how we behave with each

other, individually and collectively. And a situation or a whole

society can produce the results of empathy - care and cooperation

- even if the people involved don't particularly feel much empathy

for each other. Let's look at some of the ways society can produce

empathic outcomes regardless.

EXAMPLES OF SYSTEMIC/CULTURAL MANIFESTATIONS OF EMPATHY

Beyond majoritarianism

Competitive winner-take-all majoritarian political dynamics oversimplify

the full range of human perspectives, jamming them all into two

polarized opposites which are then pitted against each other in

search of that precious 50%+1 majority required to win dominant

political power. This creates a context in which ambitious power-seekers

can easily set us against each other with increasing intensity.

It feeds the partisan polarizing dynamics that lead us to demonize

"the other side" and make it hard to create alliances

"across the gap". (More detailed discussion of the dynamics

of polarization can be found here

and here.)

In contrast,

the use of random selection bypasses partisan oversimplifications:

in randomly selected groups, citizens find themselves face to face

with people who in some ways may be very different from them, but

they meet as fellow citizens, not as political partisans. In

citizen deliberative councils or citizen

legislatures using random selection, these citizens are then

given full-spectrum (rather than one-sided) information and helped

to talk and think together to find solutions that make sense to

the vast majority of them. In the process, they find themselves

practicing empathy without even knowing it, simply because they

need to truly hear each other and take each other's needs and experiences

into account in order to carry out their assigned task of creating

policy recommendations for their community or country.

Some methods like Dynamic Facilitation

involve "a designated listener" - a trained facilitator

who is especially good at empathizing with everyone in the group,

one by one, so they all feel heard and become increasingly able

to hear and empathize with each other. Other approaches like transpartisanship

engage admitted partisans in explicit searches for their areas of

agreement which, it often turns out, are far more common and encouraging

than most people realize. In any case, such political conversations

and institutions run directly counter to the institutionalized partisan

battles and polarization that the majoritarian system leans towards

naturally and that demagogues so readily exploit for their own divide-and-conquer

purposes. People end up empathizing even if they are not individually

particularly inclined to do so or practiced in its nuances.

Beyond reductionist global capitalism

Because money doesn't measure everything of value and more money

is always needed to pay back interest on loans, interest creates

scarcity - and this creates divisions between the haves and the

have-nots. For the same reason, interest drives "economic growth";

each person and company has to make more money than they borrowed

in order to pay back the loan. Economic growth, in turn, demands

the non-empathic exploitation of human and natural resources in

service to "the bottom line". Interest-generated scarcity

magnifies the natural competitiveness of the free market and

the non-productive global casino of purely financial speculation.

The global financial casino tends to involve both high risk and

high returns while trading imaginary economic products - e.g., bets

about the future, minor shifts in the relative value of different

countries' currencies, and various other "derivatives"

that provide little or no support to truly productive activity while

endangering resources needed by those truly productive activities.

These casino transactions are carried out in nanoseconds by computer

algorithms disconnected from any human judgment or feeling.

Furthermore, capitalism traditionally focuses on money and monetary

institutions such as a corporation's fiduciary responsibility to

generate monetary profits for its stockholders, or the dominant

economic statistic (Gross Domestic Product, or GDP) which measures

how much money is spent in an economy. Such institutions strengthen

monetary exchange relationships while undermining non-monetized

empathic gifting, sharing, and caring relationships. These capitalist

dynamics create contexts in which it is often advantageous to not

care about those on the other side of the economic game or lower

in the landscape of privilege. Too much empathy or expressions of

emotion can actually put an economic player at a disadvantage in

the competitive marketplace. However, the principle of "putting

oneself in another's shoes" IS used in advertising and marketing,

where scientific research identifies consumers' emotional responses

so that those responses can be used to get people to buy things

or otherwise act to the benefit of the corporations (or politicians)

doing the advertising.

Gifting, sharing, and caring are, in contrast, major economic activities

associated with empathy: We give and share naturally with our families

and friends. More generally we know what it is like to lack things

we need and want, so that we are naturally inclined to work together

to satisfy our various individual and collective needs using whatever

we have among us to give, share, or lend. Our present monetized

economy doesn't support this inclination towards mutual aid, since

it needs people to buy - and feel they need to own - their own consumer

products in order to keep the economy expanding. Thus more and more

"stuff" needs to be created to meet this perceived "need"

- a dynamic that is destroying the earth.

However, the increase of gifting and sharing presents an alternative

empathy-based economic vision that offers a major challenge to that

dominant capitalist model. The realization of this "new

economics" is facilitated by specially designed online

networks and inspired by economic hard times, by books like Charles

Eisenstein's Sacred Economics

and by visionary websites like Shareable.net.

We can see a kind of race between this emergent and more sustainable

economics and the dominant economics which is generating massive

inequalities while undermining both empathy and the political, social

and natural "commons" - the democracy, community, and

biosphere - upon which we all depend.

Free market capitalism seems to sense this challenge and is itself

struggling to change in ways that make it more empathic. At the

shallowest level we find traditional philanthropic activities and

efforts to reduce wealth inequality, often through taxation and

sometimes by restraining non-productive financial transactions or

providing "safety nets" for the poor. Recent research

has even demonstrated the economic value of relative wealth equality

even for capitalists.

At deeper systemic levels, we find efforts to institutionalize "the

triple bottom line" and "the public benefit corporation"

- both of which expand corporate responsibility beyond financial

return to ensure corporate activities also benefit the people and

environments they impact. Total

Corporate Responsibility goes further, engaging corporations

in changing the systems that shape the marketplace itself. At a

more fundamental level we find the localization movement in which

producers and consumers tend to know each other in the same community

and be mutually beholden to each other, as we see in Community

Supported Agriculture - an economic shift that also reduces

energy use by reducing the need to transport so many products over

great distances. Another aspect is the cooperative

movement in which those who patronize or work in a business

- or live in multi-person housing - own it, and need to work together

empathically to manage it. At the macro-economic scale we find efforts

to replace or augment GDP with better

measures of quality of life.

Perhaps the most potent empathy-related new economy design principle

- but one of the most difficult to fully understand and apply -

is the idea of internalizing

the social and environmental costs of a product in its price.

This innovation - of which a carbon tax is the most familiar example

- inspires consumers to buy the least harmful product simply because

it costs less. With this fundamental change, a free market filled

with deal-hunting consumers and corporations would end up healing

the world instead of destroying it, reducing suffering and degradation

without any exercise of empathy needed on the part of consumers

and corporations.

Two other radical proposals that embed empathic dynamics right into

the economic system include negative

interest (through which generosity serves self-interest more

than hoarding because one's money is worth less and less over time,

while one's empathic reputation earns one future support from others)

and a guaranteed

minimum income (which frees everyone to live the lives they

want).

In such economies we find greater equity and balance both in social

power relations and in quality of life, as well as more sustainability

and resilience. It is easier for people to relate to each other

- and the economies are designed so that even people's self-interest

motivates them to do well by their fellows. Having more of what

they truly need, they are also less apt to demean others in their

efforts to strengthen their own security. Their security is more

fundamentally rooted in their reputation for generosity: When they

run into hard times, people will help them in proportion to how

much they helped out others when they were better off.

With these examples I focus on political and economic spheres because

of the dominant influence they have in our lives. But obviously

other sectors can embody empathy as well. Education can be free

and responsive to the needs of the students, introducing people

to unfamiliar perspectives and cultures and training them in techniques

of empathic relationship, especially listening. Justice systems

can use more mediation and practices

that restore community and relationships rather than focusing

on punishment. Science can focus on supporting mutually beneficial

and sustaining relationships with each other and nature, rather

than increasing our ability to predict, manipulate, and control

the world around us. The opportunities for building empathy-based

cultures are virtually unlimited.

These examples provide just a taste of the kinds of social transformation

implied by seeking to co-create a culture based on empathy. Embedding

empathy in our political, economic and other systems can reduce

the harms generated by current systems while buying time to enhance

the personal experience and practice of empathy in and among all

the individuals who live in those social systems.

That is the challenge of big empathy:

1. to widen our "circle of care" to include more beings

of more species over greater time periods;

2. to become better practitioners of empathy; and

3. to embed empathy in our cultures and social systems.

If we successfully pursued all of these, it would clearly make all

the difference in the world.

See also

Big Empathy Outline

Empathy

Big Empathy: Creating

a Wise Democracy and a Caring Economy (mp3)

Home || What's

New || Search || Who

We Are || Co-Intelligence

|| Our Work || Projects

|| Contact || Don't

Miss || Articles || Topics

|| Books || Links

|| Subscribe || Take

Action || Donate || Legal

Notices

If you have comments about this site, email cii@igc.org.

Contents copyright © 2015, all rights reserved, with generous

permissions policy (see Legal Notices)

|